The History of Vermilion's Library

One hundred years ago, Vermilion’s first public library was officially established when the Vermilion school board appointed a new board of trustees to oversee a town library.

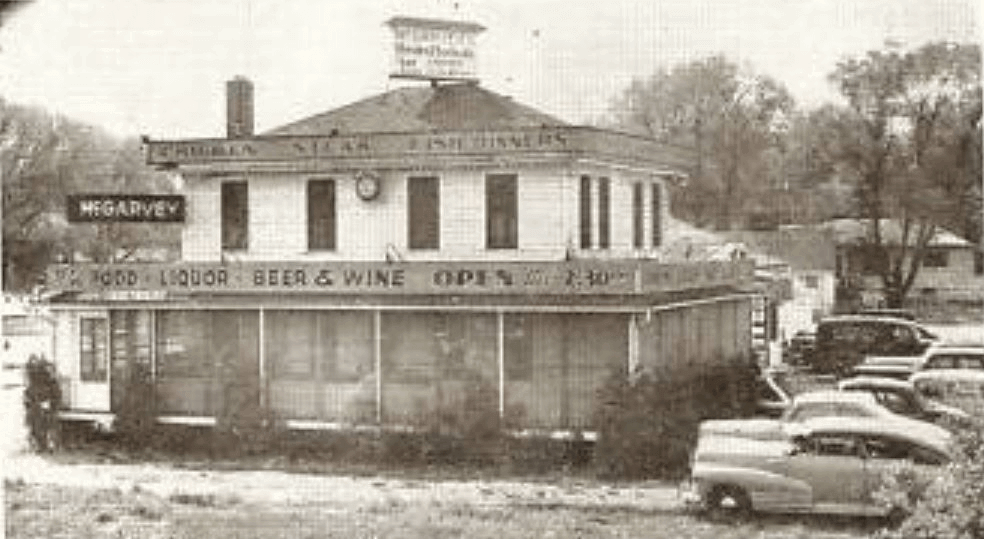

One hundred years ago, Vermilion’s first public library was officially established when the Vermilion school board appointed a new board of trustees to oversee a town library.The History Of McGarvey's

Lester A. Pelton

Lester Allan Pelton (September 5, 1829 – March 14, 1908), considered to be the father of modern day hydroelectric power, is one the most famous inventors of American history. Pelton invented the impulse water turbine. Lester Pelton was born in Vermillion, Ohio in 1829. His father was a farmer. He lived on Risden Road and attended the Cuddeback School on the northwest corner of Risden and Lake Roads. He had seven siblings. His grandfather, Captain Josiah S. Pelton, located in Vermilion in 1818. In ill health, his oldest son, Josiah S. Jr., assumed the role of family patriarch. The family prospered and all figured prominently in the development of Vermilion in business and government. But it was Lester who would become world famous.

Lester Allan Pelton (September 5, 1829 – March 14, 1908), considered to be the father of modern day hydroelectric power, is one the most famous inventors of American history. Pelton invented the impulse water turbine. Lester Pelton was born in Vermillion, Ohio in 1829. His father was a farmer. He lived on Risden Road and attended the Cuddeback School on the northwest corner of Risden and Lake Roads. He had seven siblings. His grandfather, Captain Josiah S. Pelton, located in Vermilion in 1818. In ill health, his oldest son, Josiah S. Jr., assumed the role of family patriarch. The family prospered and all figured prominently in the development of Vermilion in business and government. But it was Lester who would become world famous.When Lester grew up he decided to travel by wagon train to California. He was a quiet person who liked to study and read books. At first he went to Sacramento and became a fisherman. He was not successful at fishing so he decided to move. He went to Camptonville in Nevada County after he heard about a gold discovery along the North Fork of the Yuba River.

In 1860 all types of mining were going on, placer, hardrock, and hydraulic. Pelton did not want to be a miner so he decided to improve mining methods. He watched, studied, and learned about methods needed to power hydraulic mining. Hardrock mines also needed power to lower the men into the mines, bring up the ore cars, and return the workers to the surface at the end of their shift. Power was also needed to operate rock crushers, stamp mills, pumps, and machinery.

At the time the steam engine was used by many mines for their main power source, but the hillsides were running out of wood and trees. The Empire Mine in Grass Valley used about twenty cords of wood a day. Pelton knew the forests were disappearing so he began thinking about inventing a water wheel. In 1878 he experimented with several types of wheels.

According to a 1939 article by W. F. Durand of Stanford University in Mechanical Engineering, "Pelton's invention started from an accidental observation, some time in the 1870s. Pelton was watching a spinning water turbine when the key holding its wheel onto its shaft slipped, causing it to become misaligned. Instead of the jet hitting the cups in their middle, the slippage made it hit near the edge; rather than the water flow being stopped, it was now deflected into a half-circle, coming out again with reversed direction. Surprisingly, the turbine now moved faster. That was Pelton's great discovery. In other turbines the jet hit the middle of the cup and the splash of the impacting water wasted energy."

As the story goes, Pelton was further inspired one day when chasing a stray cow from his landlady’s yard. He hit the cow on the nose with water and the water split, circled the cows nostrils and came out at the outer edge. This gave him an idea. He rushed to his workshop and began to make a water wheel with split metal cups. The wheel was proven to be the best and most efficient in a competition. The Nevada City Foundry began to manufacture the wheels and ship them all over the world.

The Pelton wheel introduced an entirely new physical concept to water turbine design (impulse as opposed to reaction), and revolutionized turbines adapted for high head sites. Up until this time, all water turbines were reaction machines that were powered by water pressure. Pelton's invention was powered by the kinetic energy of a high velocity water jet.

A patent was granted in 1889 to Pelton, and he later sold the rights to the Pelton Water Wheel Company of San Francisco. Today Pelton wheels are used worldwide for hydroelectric power with not much change in design from the original wheels. Later evolutions of the Pelton turbine were the Turgo turbine, first patented by in 1919 by Gilkes, and the Banki turbine. Pelton was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame. His invention is on display in museums throughout the world, including the Smithsonian.

Pelton and his family are buried in Maple Grove Cemetery on Mason Road in Vermilion, Ohio. His birthplace home has been fully restored by Tom and Jean Beach. The Lester Allan Pelton Historical marker is located at Cuddeback Cemetery, Risden and Lake Roads, Vermilion Township. The marker reads: "Lester Allan Pelton" Lester Allan Pelton, "the Father of Hydroelectric Power," was born on September 5, 1829, a quarter of a mile northwest of this site. He spent his childhood on a farm a mile south of this site and received his early education in a one-room schoolhouse that once sat north of this site. In the spring of 1850, he and about twenty local boys, left for California during the great gold rush west. Pelton did not find gold, but instead invented what was commonly known as "the Pelton Water-Wheel," which produced the first hydroelectric power in the Sierra Nevada Mountains in California in 1887. The Water-Wheel was patented on August 27, 1889. Currently variations of it are still commonly used to generate electric power throughout the world. Pelton died in California on March 14, 1908. He is buried at Maple Grove Cemetery in Vermilion.

Capt. Austin & The Friendship Schooner

During the Revolutionary War in the late 1700s many Connecticut residents were burned out of their homes by the raiding British. To compensate these citizens for their losses, the Connecticut Assembly awarded the "Sufferers" 500,000 acres in the western most portion of the Western Reserve, which came to be known as the Firelands. Settlement was slow due to the remoteness of the tract and the difficulties in reaching it. Capt. William Austin, of New London Connecticut, was one of the first settlers in Vermilion. He arrived with his family in 1809 and built a home a half mile west of the mouth of the Vermillion River which flows into Lake Erie. His wife, Elizabeth, was the first white woman in Vermilion.

During the Revolutionary War in the late 1700s many Connecticut residents were burned out of their homes by the raiding British. To compensate these citizens for their losses, the Connecticut Assembly awarded the "Sufferers" 500,000 acres in the western most portion of the Western Reserve, which came to be known as the Firelands. Settlement was slow due to the remoteness of the tract and the difficulties in reaching it. Capt. William Austin, of New London Connecticut, was one of the first settlers in Vermilion. He arrived with his family in 1809 and built a home a half mile west of the mouth of the Vermillion River which flows into Lake Erie. His wife, Elizabeth, was the first white woman in Vermilion.The greater part the lake’s southern shore was at one time occupied by a tribe of Indians called the Eries. The word translates to ‘cat’, likely in reference to the wild cat or panther that once roamed the area. The lake was referred to as “Lake of the Cat” by the Indians. Vermilion was named by Native Americans for the red clay along the river banks. Oulanie Thepy (Red Creek) in the Indian’s language was translated by early French explorers as “Vermilion River.”

Capt. William Austin was a man of energy and built the first schooner along the river in 1812. She was the “Friendship”, a schooner of the times, about a fifty footer registered at 57 tons in Cleveland in 1817. Where the ship was built is not exactly known but the builders chose a flat place along the riverside. This most certainly had to be near the foot of Huron Street where the later shipyard stood when ship building became the main industry in the village. Small schooners were ideal for scudding along the lake shore bringing in supplies from Buffalo and other ports. They were as large as the natural river bars would allow and enough cargo capacity to supply the needs of the early settlements.

Mr. Austin, a Master Seaman, made nineteen trips a year to Newfoundland, Canada and Spain. He was known for having visited every port on the globe.

Many settlers left the area during the War of 1812 and did not return until after Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry's victory over the British fleet. Capt. Austin was not one of them. He remained in Vermilion and sailed the famous “Friendship” during and after the War of 1812. He carried soldiers to the battle on the Peninsula. This famous naval battle was fought in the waters of Lake Erie just a few miles from South Bass Island. It marks the only time in history that a British naval fleet ever surrendered and inspired the Star Spangled Banner and the song we know today as our National Anthem.

In 1821 Capt. Austin built the first stone house in Vermilion. He opened the first public house at or near the mouth of the Vermillion River. The first religious meeting in Vermilion was held at his home.

The captain was a very genial man, but it was unsafe to cross him. His rule aboard his ship was to have everything in its place. Any deviation from this rule resulted in certain punishment.

He would never admit to flatteries and was as outspoken and abrupt as honest. On one occasion when a man attempted to get favor by appealing to his pride, saying to him how obliging and clever a man he was, the captain replied, "CLEVER!, CLEVER! SO IS THE DEVIL SO LONG AS YOU PLEASE HIM."

He was a full believer in premonitions and warnings from unseen agents, and believed he was always warned of danger by a raving white horse in his dreams.

Around 1814 he was on his way to Detroit with several merchants as passengers. It was a delightful Indian summer day. On the way to the Islands the old white horse paid him a furious visit in his sleep, and about noon he tied up in Put- Away- Bay. The passengers were indignant; fine day, fair wind, and nothing to hinder but the old man's obstinacy or laziness. But he was immovable, not a foot would he stir out of the harbor that day. Just after nightfall came a furious snow storm and gales which so frequently destroyed ships and numerous lives on Lake Erie. In the morning the deck was covered with a foot of snow, and the wind was blowing a hurricane outside the harbor. His passengers were now very thankful for the escape, and the next day with a fair sky they landed safely in Detroit.

Once as he was returning to America, the ship making good way with a favorable wind, he retired after dinner and fell asleep. The old white horse came, with mouth wide open and in great fury. The captain bounded from his bunk, hastened to the deck, and sang out "about ship in an instant!" The order was instantly obeyed and when the ship rounded the fog, the breakers were less than eighty rods ahead, and the iron bound coast of Labrador in plain sight just beyond. Ten minutes more and "we would have never been heard of again" said the captain.

Under the protection of his white horse, Capt. Austin never met with a serious disaster, and had escaped very many.

28 years after Capt. Austin built the legendary “Friendship” schooner, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers built the two piers at the mouth of the river which provided the bar depth builders needed to take crafts to sea. Thus began the "Golden Age" of ship building on the river, in tune with the great demand for shipping on the lakes. In a period of 36 years 48 large lake schooners were built. This provided jobs and growth for the community. The harbor was a beehive of activity and the sound of the maul on caulking iron was a musical note that rang throughout the valley. The schooner was the "work horse" and a very important transportation means in the opening of the vast Great Lakes Country. They reigned supreme until a new form of transportation arrived along shore, the steam railroad.

Capt. William Austin couldn't have known in 1812 that his ship would become a cherished symbol of a town that had not yet even been incorporated. The “Friendship” schooner flies on Vermilion’s official flag and welcomes visitors on our city signage.

Phoebe Judson: Pioneer

Phoebe Goodell Judson grew up in Vermillion, Ohio. Her pioneer story begins when she married her husband Holden Allen Judson. After three years of matrimony they both decided "to obtain from the government of The United States a grant of land that "Uncle Sam" had promised to give to the head of each family who settled in this new country." With this the Judson's set out to pursue the vast uncultivated wilderness of the Puget Sound, which at that time was a part of Oregon. They departed March 1,1853. As Pheobe Judson recollects, "The time set for departure was March 1st, 1853. Many dear friends gathered to see us off. The tender "good-byes' were said with brave cheers in the voices, but many tears from the hearts."

Phoebe Goodell Judson grew up in Vermillion, Ohio. Her pioneer story begins when she married her husband Holden Allen Judson. After three years of matrimony they both decided "to obtain from the government of The United States a grant of land that "Uncle Sam" had promised to give to the head of each family who settled in this new country." With this the Judson's set out to pursue the vast uncultivated wilderness of the Puget Sound, which at that time was a part of Oregon. They departed March 1,1853. As Pheobe Judson recollects, "The time set for departure was March 1st, 1853. Many dear friends gathered to see us off. The tender "good-byes' were said with brave cheers in the voices, but many tears from the hearts."Born Phoebe Newton Goodell on October 25, 1831, Phoebe was born in Ancaster, Canada, the second eldest of eleven children with her twin sister Mary Weeks Goodell, and named after her father's sister, Phebe Goodell. Her parents were Jotham Weeks "J. W." Goodell, a Presbyterian minister descended from British colonists, and Anna Glenning "Annie" Bacheler. In 1837 her family emigrated to Vermilion, Ohio, where she and her siblings where raised.

On June 20, 1849, at the age of 17, Phoebe married Holden Allen Judson (born mid-1827), with whom she had grown up. (Holden's only sibling, Lucretia "Trecia" Judson, had been a close friend of Phoebe's in Vermilion.) The Judsons lived in Holden's parents' home in Vermilion. Their first child, Anna "Annie" Judson, was born the following year.

Following the Donation Land Claim Act, the Goodells traveled to the Oregon Territory in 1851, leaving Phoebe and her elder brother William behind. Phoebe's twin sister Mary and her fiancé Nathan W. Meloy settled in Willamette, Oregon and J. W. Goodell named and established the town of Grand Mound, Washington with his wife and younger children, where he took up a job as postmaster and part-time minister alongside George Whitworth.

Inspired by her family, and Holden's desire for independence from his parents, Phoebe set off for the month-old Washington Territory with Holden and Annie on March 1, 1853, a few days following her brother William's wedding to Maria Austin, both of whom would take the same Westward route the following year and witness the Ward Massacre. They left Ohio and, traveling on the Overland Trail once they passed Kansas City, made their way west with a small party of others. The journey in and of itself was an adventure given the primitive conditions and threat of an Indian attack. But late in June the party did pause for a day at La Bonta Creek in southeastern Wyoming when Phoebe gave birth to a son, Charles LaBonta Judson.

Phoebe Judson was the first non-Indian woman to settle in the Lynden area and became known as the "Mother of Lynden" during the half century that she lived there.

Pioneering in Washington Territory

The Judsons arrived at their new home in Grand Mound (Thurston County) in October 1853. About 1856 they moved to near Claquato (Lewis County) and late in 1858 moved to Olympia when Holden was elected to the territorial legislature on the Democratic ticket. They would remain in Olympia for nearly eight years. Holden served at least two terms in the legislature, and subsequently operated a store in Olympia.

In 1866 the Judsons moved to Whidbey Island, where Holden may have operated another store. By the end of the 1860s, their biological family was complete. They had four children: Annie (1850-1937), Charles (1853-1933), George (1859-1891), and Mary "Mollie" (1862-1894). (A fifth child, Carrie, died of whooping cough one month and one day after birth in 1869.) But note the distinction "biological family," because the Judsons would subsequently adopt an additional 11 children.

On March 1, 1870, the Judsons left Whidbey Island, bound for Lynden. They traveled by the steamer Mary Woodruff to Whatcom (now part of Bellingham), then obtained three canoes, with two Indians apiece, to paddle, pole, and portage them up the Nooksack River to Lynden.

The Judsons moved into a rough log cabin that they had acquired in an unusual trade with Colonel James Alexander Patterson, the first white settler in Lynden. Patterson had built the cabin in 1860, and he and his Native American wife had lived there for most of the decade. But at some point in the late 1860s his wife left him, and he began to search for a foster home for his two young daughters. By this time he was a frequent visitor to the Judson’s home on Whidbey Island. Patterson made an offer to the Judsons that he would swap his home and land in what was then known among the settlers as "Nooksack" or "Nootsack" if the Judsons would care for his two daughters, Dollie (age 7 in March 1870) and Nellie (age 4 in March 1870) until they came of age. The Judsons agreed, and Patterson executed a quitclaim deed to his land in favor of Phoebe Judson in March 1870.

The Judsons settled into what Phoebe Judson would famously refer to as her "ideal home." It was located just south of 6th and Front streets, near the southwestern edge of today’s Judson Street Alley, and had a view of the Nooksack River, which at the time ran farther north than it does today. Holden became postmaster of Lynden in 1873, and Phoebe was asked to select the name of the new town. She chose a name that she had heard from a poem, Hohenlinden, written by Thomas Campbell, which begins "On Linden, when the sun was low ..." But she changed the "i" in Linden to "y" because she felt it looked prettier.

Aunt Phoebe, the Mother of Lynden

Since Phoebe Judson was the first white woman in Lynden, she became known as the "Mother of Lynden," and her presence in the community was established. Almost from the beginning she was called "Aunt Phoebe," someone you went to when you needed something, be it a pail of buttermilk or help during childbirth. She also became known for writing letters to the Bellingham Bay Mail during the 1870s, describing the joys of life as a "Pioneer’s Wife," as she usually signed her letters.

But she was more that that. She took a considerably more active role in the community than did many women of the day. During the 1870s log jams plagued the Nooksack River, preventing steamers from making their way upriver to Lynden. One of the biggest jams was downriver from Lynden, near what is today Ferndale. In March 1876 Phoebe began to solicit funds for the removal of the jam. Aided by a $50 donation from Holden, $1,500 was raised by the end of April from settlers in Sehome and Whatcom (both now part of Bellingham) as well as from settlers along the river. Phoebe also suggested that the man who donated the most work on the jam be given votes for a county office. History doesn’t record whether or not this happened, but work on the jam began, and it was gone by early 1877.

Phoebe’s son George Judson platted Lynden in 1884, and as the town site developed, the Judsons donated parts of their land for churches, schools, a printing office, a blacksmith shop, and for various private purposes. They also built the Judson Opera House in the late 1880s, and when it was completed in 1889 it became the community nexus for lectures, entertainment, and celebrations.

Phoebe has been described as a gregarious crusader for many causes. Known as religious, she took an active role in her opposition to saloons in early-day Lynden. But she is also known for taking an active role in the early development of its churches and schools. She arguably became more well-known than her husband, Holden, perhaps because she outlived him by 26 years and had the opportunity to accomplish more, and perhaps also because of her book of her life, A Pioneer’s Search for an Ideal Home, which was first published in 1925, the year before her death.

During the 1880s the Judsons moved to a new two-story frame home on the north side of Front Street, midway between 5th and 6th streets. Holden died there on October 26, 1899, and Phoebe peacefully passed away there on January 16, 1926, having remained physically active and mentally alert until the time of her death. Services were held two days later, and the entire city of Lynden shut down to mark the occasion: Stores were closed, schools were dismissed, and hundreds of people from miles around made the pilgrimage to pay final tribute to the "Mother of Lynden."

The Simon Kenton Boulder

One of the first explorers of the Vermilion area was Simon Kenton (April 3, 1755 - April 29, 1836,) a famous United States frontiersman and friend of the renowned Daniel Boone, the infamous Simon Girty, and the valiant Spencer Records.

One of the first explorers of the Vermilion area was Simon Kenton (April 3, 1755 - April 29, 1836,) a famous United States frontiersman and friend of the renowned Daniel Boone, the infamous Simon Girty, and the valiant Spencer Records. Simon Kenton was born in the Bull Run Mountains, Prince William County, Virginia to Mark Kenton Sr. (an immigrant from Ireland) and Mary Miller Kenton. In 1771, at the age of 16, thinking he had killed a man in a jealous rage, he fled into the wilderness of Kentucky and Ohio, and for years went by the name "Simon Butler."

Kenton served as a scout against the Shawnee in 1774 in the conflict between Native Americans and European settlers later labeled Dunmore's War. In 1777, he saved the life of his friend and fellow frontiersman, Daniel Boone, at Boonesborough, Kentucky. The following year, Kenton was in turn rescued from torture and death by Simon Girty.

Kenton served on the famous 1778 George Rogers Clark expedition to capture Fort Sackville and also fought with "Mad" Anthony Wayne in the Northwest Indian War in 1793-94.

In 1782, he returned to Virginia and found out the victim had lived and readopted his original name.

In 1784 Kenton chiseled his name, S. Kenton 1784, on a boulder about 2 miles south of the Vermilion River mouth on the southern border of the old Rossman farm in a spot about 600' east of the State Road.

Presumably, Kenton marked the boulder to substantiate his claim to a 4 square mile area surrounding the river mouth, a likely settlement someday. Kenton claimed similar areas throughout the State but lost his claims due to his lack of education. He was too early and too ignorant of drawing up legal claims of his discoveries.

We do have the satisfaction of knowing that he was the first to find and realize that the Vermilion River would some day be the nucleus of a growing community. How right he was!

In 1937 the Vermilion Centennial "Stone Committee" discovered the stone. The stone now stands as a memorial to Kenton at the Ritter Library.

Kenton moved to Urbana, Ohio in 1810, and achieved the rank of brigadier general of the Ohio militia. He served in the War of 1812 as both a scout and as leader of a militia group in the Battle of the Thames in 1813.

Simon Kenton had 6 children in his second marriage. Kenton died in New Jerusalem, Ohio (in Logan County) and was first buried there. His body was later moved to Urbana, Ohio.

He died a poor man and might have been governor if he had had the proper background. As it was, though, he was an outstanding explorer in the Ohio wilderness and his efforts added considerably to the opening of the country to the settlers.

The History of VOL's Historic Ballroom

In 1919 a group of investors from the Cleveland area purchased a wooded property with 600 feet of Lake Erie frontage in tiny “Vermilion-on-the-Lake”, Ohio. They cleared the land, and using the very logs they felled, built an approximately 10,000 square foot private community center known as the Vermilion-on-the-Lake Clubhouse.

In 1919 a group of investors from the Cleveland area purchased a wooded property with 600 feet of Lake Erie frontage in tiny “Vermilion-on-the-Lake”, Ohio. They cleared the land, and using the very logs they felled, built an approximately 10,000 square foot private community center known as the Vermilion-on-the-Lake Clubhouse.

The big bands of that era were soon accompanied by couples dancing on polished hardwood floors beneath a glittering globe. Those original hardwood floors, framed by the original log walls, are still there today. Soon, “Vermilion-on-the-Lake” became a summer playground and a sparkling jewel for well-to-do residents of western Cleveland.

These pre-Depression era high rollers purchased summer cottages throughout the area and shared access to the clubhouse’s 600-foot pristine and sandy beach. Ladies with parasols strolled the boardwalk of the “Atlantic City of the Midwest”. As late as the 1950’s, top-notch entertainment attracted society’s elite to the “V.O.L.” to see the big bands of the day, including the leading edge sounds of the “Chuck Berry Trio” performing their hit “Maybellene” one summer Tuesday night in 1955.

But, alas, the luster faded. Rising lake levels reclaimed the pristine beach, the economy turned sour and many lot owners looked to sell. Maintenance waned and the original owners agreed to deed the property over to the “Vermilion-on-the-Lake Lot Owners Association”.

During the 1960’s “Vermilion-on-the-Lake”, which had been an incorporated village, was annexed by the then “Village of Vermilion” to create the current “City of Vermilion”.

The VOL (Vermilion-on-the-Lake) Historic Community Center remains today one of the only wedding venue's still situated on Lake Erie's shore. The 'VOL CLubhouse', as it has been called, demands only modest rental fees which assist the effort to save and renovate this historic building.

The Vermilion-on-the-Lake Historic Community Center Charitable Trust is a non-profit corporation formed under the laws of the State of Ohio as a service organization. Besides the restoration and operation of the Historic Community Center, their mission includes community service, involvement in the security of the area through our "Block Watch" program, providing a venue for community fellowship and political discussion, and providing education to our citizens about the history and culture of our area.

Through an affiliation with the Lorain County Historical Society, they seek to emphasize the historic nature of this unique building and encourage the businesses and foundations tasked with preserving our heritage to lend a hand in restoring the Historic Community Center to its once glorious condition.

VOL Historic Community Center is located at 3780 Edgewater Blvd, Vermilion, Ohio 44089.

The History Of The Vermilion Lagoons

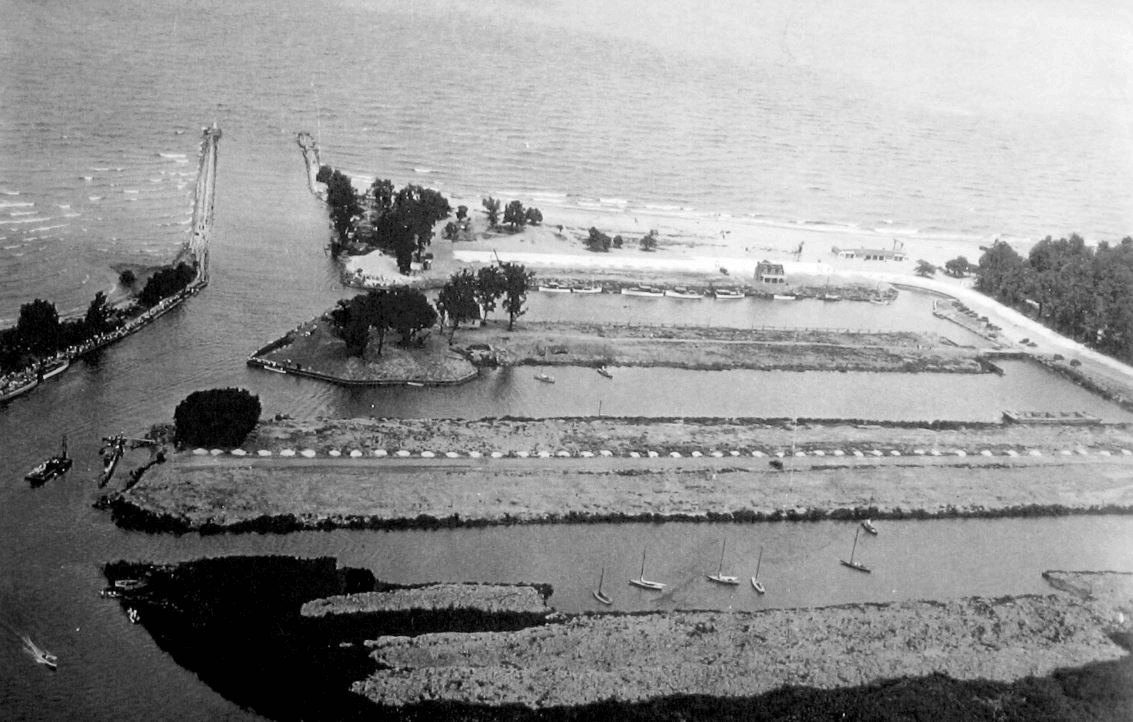

Louis Wells, a Cleveland contractor, began the Vermilion Lagoons project as a means of keeping his men busy during the Great Depression of the 1930s. By 1931 the first house and the beach house had been built and the lagoons were dredged and most of the wooden piling secured.

Louis Wells, a Cleveland contractor, began the Vermilion Lagoons project as a means of keeping his men busy during the Great Depression of the 1930s. By 1931 the first house and the beach house had been built and the lagoons were dredged and most of the wooden piling secured.East Charity Shoal Lighthouse

The steamship Rosedale was built at Sunderland, England in 1888 and on her maiden run completed the first ever direct voyage from London to Chicago via the St. Lawrence River and Welland Canal. This accomplishment caused great excitement in the American maritime community, as it proved that grains from the elevators in Chicago, and other ports on the Great Lakes, could be shipped to London without transshipment. Though her first sailing caused a stir, every trip did not turn out quite so well. On December 5, 1897, the Rosedale grounded upon the rocks of East Charity Shoal during a northwest gale. The vessel was abandoned to her underwriters, but was eventually towed off by a wrecking company, and, after being rebuilt, returned to service.

The steamship Rosedale was built at Sunderland, England in 1888 and on her maiden run completed the first ever direct voyage from London to Chicago via the St. Lawrence River and Welland Canal. This accomplishment caused great excitement in the American maritime community, as it proved that grains from the elevators in Chicago, and other ports on the Great Lakes, could be shipped to London without transshipment. Though her first sailing caused a stir, every trip did not turn out quite so well. On December 5, 1897, the Rosedale grounded upon the rocks of East Charity Shoal during a northwest gale. The vessel was abandoned to her underwriters, but was eventually towed off by a wrecking company, and, after being rebuilt, returned to service. During the summer of 1900, John C. Churchill, Jr. visited Charity Shoal to survey and chart the outlying spur known as East Charity Shoal. This hazard, which was about 3,000 feet long and at some points covered by just ten feet of water, lay in the line of transit for vessels using the St. Lawrence River and was thus a great peril to navigation. Later that year, the Lighthouse Board moved to mark the obstacle and issued the following Notice to Mariners: “Notice is hereby given that a nun buoy painted red and numbered 2 has been placed in twenty feet of water to mark the easterly edge of East Charity shoal, Lake Ontario, New York. This buoy is about 1 3/8 miles E.S.E. of Charity shoal gas buoy. It is recommended that vessels bound to or from the main channel of the St. Lawrence river, and using the passage between Galloo and Main Duck Islands, should keep to the eastward of this buoy.”

This navigational buoy didn’t prevent all mishaps, as in October of 1912 the steamer Rock Ferry ran aground on East Charity Shoal, and tugs had to be dispatched in an attempt to free her. The Lighthouse Service eventually opted for a more permanent method of marking the shoal, and in May of 1934 newspapers in upstate New York advertised that sealed proposals would be accepted by the Superintendent of Lighthouses in Buffalo for a “timber crib-concrete superstructure” on East Charity Shoal.

The Walls Company was selected as the contractor for the project and had completed enough of the structure so that a temporary light was established on the south side of the crib on November 24, 1934. The foundation consisted of a fifty foot square crib, whose height varied from eleven to fourteen feet to fit the shoal. Constructed ashore in an inverted position, the crib was launched, righted, towed to the site, and sunk in place using stone and interlocking blocks of pre-cast concrete. A reinforced concrete slab was placed over the entire pier and atop this a one-story deckhouse, also of reinforced concrete and octagonal in form, was built to support an octagonal iron tower. After the tower was installed on the deckhouse in 1935, a fourth-order Fresnel lens was placed in the tower’s lantern room and, using acetylene as the illuminant, a 1,300 candlepower light was produced at a focal plane of fifty-two feet above low water depth. The entire project, including riprap to protect the foundation, cost $95,125.

The octagonal iron tower at East Charity Shoal has the distinction of having served at two stations and on two different Great Lakes. It was first installed in 1877 at the end of a pier in Vermilion, Ohio to mark the entrance to the Vermilion River from Lake Erie. After the beacon had been in service for over fifty years, two teenage brothers, who lived next to the harbor, noticed that the lighthouse had developed a lean after the pier had been damaged by an ice storm. The father of the two boys contacted the Lighthouse Service, and not long thereafter the heavy tower was replaced by a much lighter automated tower.

The residents of Vermilion were fond of the old red and white pierhead beacon, and when the octagonal tower was taken away it was as if a member of the community had been lost. Years later, after his childhood home had been converted into the Inland Seas Maritime Museum, Ted Wakefield, one of the two boys who had noticed the lean, championed a fundraising drive to build a replica of the 1877 tower for the museum grounds. His dream was realized during the summer of 1991, when a crane lifted the newly cast tower onto its prepared foundation overlooking Lake Erie.

For years, Vermilionites did not know the fate of the 1877 lighthouse. Most thought it had ended up on the scrap heap, but the real answer was revealed to Vermilion when Olin M. Stevens, of Columbus, Ohio, visited the Inland Seas Maritime Museum. Stevens came seeking additional information on his grandfather, Olin W. Stevens, who was a third generation lighthouse keeper, and when he learned the museum was trying to determine the fate of the 1877 tower, he realized he had just recently found the answer. While searching for information on his ancestors to give to his grandchildren, Stevens opened an old trunk and discovered a newspaper article that told about the service of his grandfather at Tibbetts Point Lighthouse. A portion of the article read, “Altho this is his first duty on Lake Ontario, Charity Shoal light, visible from the Tibbett's Point headland, is an old friend. The tower upholding the gas lamp on Charity formerly was under Keeper Stevens’ charge at Vermilion, near Lorain. Victim of an ice shove, it was salvaged and taken to Buffalo, where it was assigned to Charity.” The mystery had been solved.

Although the East Charity Shoal Lighthouse was never manned, it was still responsible for saving the life of at least one individual. Dr. Joseph G. Reidel, a 37-year-old physician from Syracuse, was sailing on Lake Ontario with his wife and Dr. and Mrs. W. Hall of Watertown on August 5, 1955, when winds estimated at 70mph struck their dragon class sloop. Dr. Reidel was washed overboard by the wind-whipped sea and for an hour was able to tread water and keep sight of the sailboat while his wife and friends desperately tried to rescue him or get him a lifejacket. Neither effort was successful, and Dr. Reidel was presumed lost. As it started to get dark, Reidel noticed the glint of a lighthouse and decided to swim towards it. Reidel swallowed a lot of water and suffered leg cramps for a stretch of forty minutes, but as he struggled to stay afloat he kept repeating to himself, “This can’t happen to me but it will unless I get there.”

After more than eight hours in the water, Reidel pulled himself up onto the pier at East Charity Shoal. Exhausted, he soon fell asleep and was rescued at 5:30 a.m. the following morning by three fishermen. Reidel was eventually taken to Cape Vincent, where he was reunited with his wife and friends.

Though alone and surrounded by a vast body of water, East Charity Shoal Lighthouse will always be cherished by the residents of Vermilion and a grateful physician from Syracuse.

In July of 2008, the East Charity Shoal Lighthouse was declared surplus by the Coast Guard and pursuant to the National Historic Lighthouse Preservation Act of 2000 was "made available at no cost to eligible entities defined as federal, state and local agencies, non-profit corporations, educational agencies, or community development organizations for education, park, recreation, cultural, or historic preservation purposes."

Copyright 2001-2008 Lighthousefriends.com

The Life of George Ritter

1877 Vermilion Lighthouse

Vermilion, Ohio straddles a river of the same name as it empties into Lake Erie, and it has a past as colorful as the clay for which the river was named. Once known as the “city of sea captains,” the city was a popular drop-off point for illegal liquor from Canada during the days of Prohibition. The city has been home not only to many captains and sailors, but also to an amazing lighthouse story that spans two centuries and two Great Lakes.

Vermilion, Ohio straddles a river of the same name as it empties into Lake Erie, and it has a past as colorful as the clay for which the river was named. Once known as the “city of sea captains,” the city was a popular drop-off point for illegal liquor from Canada during the days of Prohibition. The city has been home not only to many captains and sailors, but also to an amazing lighthouse story that spans two centuries and two Great Lakes. Inhabited by the Erie Indians as early as 1656, Vermilion had grown large enough by the mid-nineteenth century for its harbor to warrant government maintenance. In 1847, Congress appropriated $3,000 to build a lighthouse and prepare the head of the pier on which it would be built. Before 1847, the people of Vermilion had constructed their own navigational aid: wooden stakes topped with oil-burning beacons at the entrance of the harbor.

By 1852, both the lighthouse and the pier were in need of repair, a project that cost $3,000. Seven years later, in 1859, the lighthouse was rebuilt at a cost of $5,000. The new lighthouse was made of wood and topped with a whale oil lamp. The lamp’s flame was surrounded by red glass, resulting in a red beam that, with the help of a sixth-order Fresnel lens, was visible from Lake Erie. A man from the town looked after the lighthouse, lighting the lamp each evening and refueling it each morning.

Though the 1859 light was functional, it was not sturdy enough for long-term use. Both time and the lake’s elements took their toll on the wooden lighthouse, and by 1866, Congress had appropriated funds to build a new light, this time out of iron, on the west pier. The lighthouse was designed by a government architect and cast by a company in Buffalo, New York. A home for the future keeper was purchased in 1871, six years before the iron lighthouse was installed.

To cast the lighthouse, the ironworkers used sand molds of three tapering rings, octahedral in shape. The iron they used was from unpurchased Columbian smoothbore canons, obsolete after the Battle of Fort Sumter. As noted by Vermilion native Ernest Wakefield, “The iron, therefore, of the 1877 Vermilion lighthouse echoed and resonated with the terrible trauma of the War Between the States.”

Once the ironworkers in Buffalo had completed the casting of the lighthouse and ensured that all parts fit together correctly, the pieces of the lighthouse were loaded onto barges in the nearby Erie Canal. Hauled by mules, the barges reached Oswego, New York, in two weeks. From there, the lighthouse was transferred to the lighthouse tender Haze. The Haze, a steam-powered propeller vessel, departed Oswego on September 1, 1877 and headed west for the Welland Canal, where a series of 27 locks raised the boat to the water level of Port Colborne and onto Lake Erie. One must wonder why this circuitous route was taken when Buffalo, where the tower was cast, sits right on Lake Erie.

On its way to Vermilion, the Haze stopped at Cleveland Harbor, where it took on the lighthouse’s lantern, lumber and lime for building the foundation, and a crew to raise the lighthouse. Also loaded was a fifth-order Fresnel lens, which had been shipped to Cleveland by train. All that is known about the lens is that it was made by Barbier and Fenestre of Paris, France. Whether it was ordered specifically for the Vermilion lighthouse or recovered from the Erie Harbor Lighthouse, no one knows.

One day later, the Haze arrived in Vermilion. It took several days to prepare the foundation, and once it was in place, the crew used the derrick on the Haze to lift the bottom ring of cast iron and place it on the foundation. After the ring was bolted down, the successive tapering rings were put into place and bolted to each other. Then the pediment and lantern were added. The Fresnel lens and oil lantern were installed later. Once completed, the tower measured 34 feet high. It stood at the end of the pier with a long 400-foot-long catwalk running above it. This allowed the lighthouse keeper to travel between the light and the mainland when large waves crested over the pier. One such lightkeeper was Captain J. H. Burns, who lived in the home purchased by the government in 1871. From this home on the corner of Liberty and Grand Street, he would walk each night to hang the lantern inside Vermilion’s lens. He would also wash the windows around the prism twice a week.

Initially, oil for the lantern was stored in the keeper’s house. It was not until 1906 that an oil shed, accommodating 540 gallons, was built just south of the lighthouse. The lamp was converted to acetylene in 1919, and then eventually into an electric beacon. Its white light would blink one second on, seven seconds off. Ultimately, it was replaced by a steady red beam.

The 1877 lighthouse performed its duties faithfully for over half a century, shining its light for both commercial and pleasure boats. During this time, it was moved closer to the end of the pier (25 feet from the outer end), and survived multiple collisions with watercraft. Eventually it was put under the care of Lorain Lighthouse’s assistant keeper, and in the early 1920s, the Vermilion keeper’s home was sold to the local Masonic Lodge.

In the summer of 1929, Theodore and Ernest Wakefield, teenagers at the time, noticed that the Vermilion Lighthouse was leaning toward the river. Most likely, the lighthouse pier had suffered damage in an icy storm earlier that year. The Wakefield boys reported what they had seen to their father, Commodore Frederick William Wakefield, who contacted the U.S. Lighthouse Service in Cleveland. The U. S. Corps of Engineers came to Vermilion and determined that the light was indeed unstable. Within a week, the lighthouse had been dismantled. In its place, a steep-sided 18-foot steel pyramidal tower was erected. The new structure, called a "functional disgrace," continued to shine a red light, but since it was automated, no lighthouse keeper was needed.

Commodore Wakefield offered to purchase the old lighthouse and move it to his property, Harbor View, but his request was denied. Instead, the cast-iron pieces were loaded up and hauled away. The residents of Vermilion were sad to see their beloved lighthouse go. No one told them what the fate of the old lighthouse would be, and its whereabouts were unknown until many years later.

Ted Wakefield, one of the young men who had noticed the lighthouse leaning in 1929, had very fond memories of Vermilion’s past and its lighthouse. As an adult, he put his efforts into encouraging downtown Vermilion to maintain its historical 19th century appearance. His childhood home, Harbor View, was donated to Bowling Green State University and later sold to the Great Lakes Historical Society. Built of gravel from Lake Erie in 1909, the old house became the main structure of the society's Inland Seas Maritime Museum. This gave Ted an idea. He decided that a replica of the 1877 lighthouse would be the perfect complement to it.

Ted spearheaded a fund-raising campaign to build the new lighthouse. Funds were raised by mailing out brochures, writing articles in the local paper, and collecting donations at the museum. By 1991, Ted and his fellow fund-raisers had collected $55,000---enough to build a 16-foot replica of Vermilion’s 1877 lighthouse. Architect Robert Lee Tracht of Huron prepared the plans, which were approved by the city, county, and state authorities, but only after a long delay. Even the U.S. Coast Guard approved the plans for making the light a working lighthouse, right down to its steady red light. Again, a company in Buffalo fabricated the lighthouse.

Ground was broken for the new lighthouse on July 24, 1991, by Mayor Alex Angney. The 25,000-pound base of the replica lighthouse, measuring 15 feet in diameter, was brought to Vermilion on a flatbed truck. Cranes were used to place it onto the foundation. According to rumors, before the base was attached to the foundation, an 1877 gold piece was placed under the vertex of the octahedron that would point true north. It seems only fitting that a piece of 1877 be part of the new lighthouse’s foundation.

The tower was raised in less than three hours on October 23, 1991. The lantern and roof were attached the next day, and a fifth-order Fresnel lens (owned by the museum) was mounted. The tower was electrically wired, and an incandescent 200-watt lamp with Edison-base was installed. A red glass cylinder surrounded the lamp to make the replica complete. The new Vermilion Lighthouse was dedicated on June 6, 1992, and is still operational today. It serves not only as part of the museum, but also as an active aid to navigation.

Shortly after their new light was built, the residents of Vermilion learned what had become of their original lighthouse. Amazingly, the structure had not been destroyed after its removal. In fact, it was still shining, and had been for the last 59 years.

Once the lighthouse had been dismantled in 1929, it was transported to Buffalo, New York, where it was renovated. Six years later, in 1935, the lighthouse was given a new home and a new charge---on Lake Ontario. Sitting off Cape Vincent at the entrance to the Saint Lawrence Seaway, the Vermilion Lighthouse was given a fifth-order Fresnel lens and renamed East Charity Shoal Lighthouse. The light remains an active aid to navigation, with its modern optic (installed in 1992) displayed at a 52-foot focal plane.

The History Of Crystal Beach Park

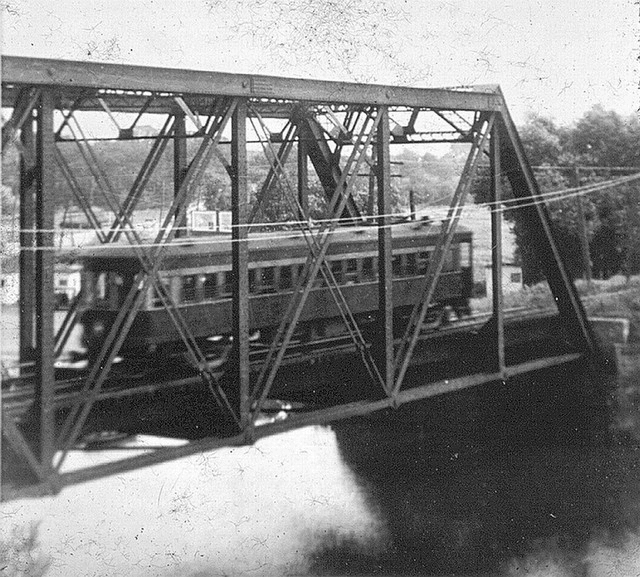

Crystal Beach Park in Vermilion first opened on Decoration Day (later renamed Memorial Day) in 1907. On this acreage, as early as 1870, stood a picnic grove called Shadduck Lake Park. This pleasant grove became popular because the tree shaded area was accessible to horse-drawn buggies.

Crystal Beach Park in Vermilion first opened on Decoration Day (later renamed Memorial Day) in 1907. On this acreage, as early as 1870, stood a picnic grove called Shadduck Lake Park. This pleasant grove became popular because the tree shaded area was accessible to horse-drawn buggies.John Mercer Langston

John Mercer Langston was one of the most extraordinary men of the 19th century. Slim and debonair, and of mixed-raced parentage, Langston was highly educated, an expert in constitutional law, a community organizer and a gifted orator who sought to unify a divided country after the Civil War. He was the first African-American elected to a local office, winning the office of Clerk of Brownhelm Township on April 2, 1855.

John Mercer Langston was one of the most extraordinary men of the 19th century. Slim and debonair, and of mixed-raced parentage, Langston was highly educated, an expert in constitutional law, a community organizer and a gifted orator who sought to unify a divided country after the Civil War. He was the first African-American elected to a local office, winning the office of Clerk of Brownhelm Township on April 2, 1855.Langston was the son of Ralph Quarles, a white plantation owner, and Jane Langston, a black slave. After his parents died when Langston was five, he and his brothers moved to Oberlin, Ohio, to live with family friends. Langston enrolled in Oberlin College at age 14 and earned bachelor's and master's degrees from the institution. Denied admission into law school, Langston studied law under attorney Philemon Bliss of Elyria. Langston became the first black lawyer in Ohio, passing the Bar in 1854. He became actively involved in the antislavery movement, organizing antislavery societies locally and at the state level. He helped runaway slaves to escape to the North along the Ohio part of the Underground Railroad.

Langston married Caroline Wall, a senior in the literary department at Oberlin, settled in Brownhelm, OH and established a law practice. He quickly involved himself in town matters. In 1855 Langston became the country's first black elected official when he was elected town clerk of the Brownhelm Township.

Langston moved to Oberlin in 1856 where he again involved himself in town government. From 1865 - 1867 he served as a city councilman and from 1867-1868 he served on the Board of Education. His law practice established and respected, Langston handled legal matters for the town. Langston vigilantly supported Republican candidates for local and national office. He is credited with helping to steer the Ohio Republican party towards radicalism and a strong antislavery position. He conspired with John Brown to raid Harpers Ferry.

Langston organized black volunteers for the Union cause. As chief recruiter in the West, he assembled the Massachusetts 54th, the nation's first black regiment, and the Massachusetts 55th and the 5th Ohio. He was a founding member and president of the National Equal Rights League, which fought for black voting rights. During the Civil War Langston recruited African Americans to fight for the Union Army. After the war, he was appointed inspector general for the Freedmen's Bureau, a federal organization that helped freed slaves. He was the first African American to practice before the U.S. Supreme Court. Selected by the Black National Convention to lead the National Equal Rights League in 1864, Langston carried out extensive suffrage campaigns in Ohio, Kansas and Missouri. Langston's vision was realized in 1867, with Congressional approval of suffrage for black males.

Langston moved to Washington, DC in 1868 to establish and serve as dean of Howard University's law school — the first black law school in the country. He was appointed acting president of the school in 1872. In 1877 Langston left to become U.S. minister to Haiti. He returned to Virginia in 1885 and was named president of Virginia Normal and Collegiate Institute (now Virginia State University). In 1888 he ran for a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives as an Independent. He lost to his Democratic opponent but contested the results of the election. After an 18-month fight, he won the election and served for six months. Langston was the first black Congress member from Virginia and a diplomat. He lost his bid for reelection.

The town of Langston, Oklahoma, and Langston University, is named after him. The John Mercer Langston Bar Association in Columbus, Ohio, is named in his honor along with Langston Middle School in Oberlin, Ohio, the former John Mercer Langston High School in Danville, Virginia, and John M. Langston High School Continuation Program in Arlington, Virginia. His house in Oberlin is a National Historic Landmark. Langston was the great-uncle of poet Langston Hughes.

It took 153 years to get from John Mercer Langston to Barack Hussein Obama, a journey that endured the dashed hopes of Reconstruction and the oppression of Jim Crow to arrive at a moment that has stunned even those optimistic about America's racial progress.

The John Mercer Langston Ohio Historical Marker is located at Brownhelm High School, 1940 North Ridge Road, Vermilion, Ohio. The marker reads: "John Mercer Langston" The first African-American elected to government office in the United States, John Mercer Langston (1829-1897) won the office of Clerk of Brownhelm Township on April 2, 1855. Born in Virginia and raised in Chillicothe, Langston graduated from Oberlin College in 1849 and was admitted to the Ohio Bar in 1854, becoming Ohio's first black attorney. He served as the first president of the National Equal Rights League in 1864, and subsequently as professor of law, dean, and acting president of Howard University in Washington, D.C. In 1890, he became Virginia's first black congressman. Throughout his career Langston set a personal example of self-reliance in the struggle for justice for African-Americans.

The History Of Woollybear

The woollybear wackiness all started more than three decades ago. Northeast Ohio TV weatherman Dick Goddard of Fox8 TV in Cleveland talked with some friends and co-workers about his idea of a celebration built around using the woollybear to forecast what kind of winter is ahead.

The woollybear wackiness all started more than three decades ago. Northeast Ohio TV weatherman Dick Goddard of Fox8 TV in Cleveland talked with some friends and co-workers about his idea of a celebration built around using the woollybear to forecast what kind of winter is ahead.The History Of The Christmas Tree Ship

Vermilion Ohio's annual Christmas Tree Ship event, when holiday trees are brought to shore by boat, is a recreation of a Great Lakes Christmas tradition that became legend when the Rouse Simmons, "The Christmas Tree Ship", sank in a November 1912 storm with a cargo full of Christmas trees. The legendary schooner, and its skipper "Captain Santa", continue to bring the spirit of Christmas ashore with annual traditions inspired by the legend of the Christmas Tree Ship.

Vermilion Ohio's annual Christmas Tree Ship event, when holiday trees are brought to shore by boat, is a recreation of a Great Lakes Christmas tradition that became legend when the Rouse Simmons, "The Christmas Tree Ship", sank in a November 1912 storm with a cargo full of Christmas trees. The legendary schooner, and its skipper "Captain Santa", continue to bring the spirit of Christmas ashore with annual traditions inspired by the legend of the Christmas Tree Ship.Captain Herman Scheunemann, center, and associates docked at the Clark Street Bridge, early 1900s.

At some stage of Herman Schuenemann's long career as a late-season tree captain, he was given the title of Captain Santa. The affectionate nickname was bestowed by Chicago's local newspapers and by the city's grateful residents. Schuenemann's profits from selling Christmas trees had never made the family wealthy, but his reputation for generosity was well established, and he delighted in presenting trees to many of the city's needy residents. Schuenemann enjoyed the sobriquet and proudly kept newspaper clippings about his role as Captain Santa in his oilskin wallet.

Over the years, Herman Schuenemann commanded several schooners that carried Christmas trees to Chicago, including the George Wrenn, the Bertha Barnes, and the Mary Collins. Like many other merchant-sailors, Schuenemann could not afford to purchase a schooner outright. It was a common practice for two or more businessmen or lake captains to form a partnership and purchase shares in a vessel. In 1910 Schuenemann purchased a partial interest in the Rouse Simmons. By 1912, Schuenemann's financial interest in the ship amounted to one-eighth of the ship, while Capt. Charles Nelson of Chicago, who later accompanied Schuenemann on the fateful November trip, owned another one-eighth share, and businessman Mannes J. Bonner of St. James, Michigan, held a commanding three-fourths interest in the vessel.

Throughout the year and especially during the winter months when the Great Lakes were impassable because of ice and storms, many lake boat captains supplemented their incomes in other ways. As a small businessman, Schuenemann not only made his living on the lake, but he also owned businesses that in 1906 included a saloon. In these business endeavors, Schuenemann did not always meet with success, and on January 4, 1907, he petitioned for bankruptcy in the U.S. District Court in Chicago. Listed as a saloon keeper, Schuenemann's debts to his creditors amounted to over $1,300, which he was unable to satisfy. This financial setback, however, does not appear to have interfered with his other role as a lake captain.

On November 9–10, 1898, tragedy marred the Schuenemann's holiday season when, just one month after the birth of twins Hazel and Pearl, Herman's older brother August Schuenemann died while sailing a load of Christmas trees to Chicago aboard the schooner S. Thal. The 52-ton, two-masted schooner, built in Milwaukee in 1867, broke up after it was caught in a storm near Glencoe, Illinois. There were no survivors. The Schuenemann family was devastated, but Herman continued the family tradition of making late-season Christmas trees runs.

District court records for Milwaukee suggest that August came to the S. Thal just weeks before his death, when it was sold at auction by U.S. Marshals to pay fees owed to Otto Parker, the vessel's 19-year-old cook. Parker sued the vessel's previous owner, William Robertson, in admiralty court over Robertson's refusal to pay Parker the remaining $66 owed for his services as cook aboard the tiny vessel. In September 1898, Judge William H. Seaman decided the case in favor of the young cook, and the vessel was sold to pay the debt.

By 1912, Schuenemann was a veteran schooner master who had hauled Christmas trees to Chicago for almost three decades. While Schuenemann was in his prime as a lake captain, the same could not be said for the Rouse Simmons. The once-sleek sailing vessel was now 44 years old and long past its peak sailing days. Time, the elements, and hundreds of heavy loads of lumber had taken their toll on the vessel's physical condition.

The Rouse Simmons, the “Christmas Tree Ship,” docked on the Chicago River in 1909.

On Friday, November 22, 1912, the Rouse Simmons, heavily laden with 3,000–5,000 Christmas trees filling its cargo hold and covering its deck, left the dock at Thompson, Michigan. Some eyewitnesses to the Rouse Simmons's departure claimed the ship looked like a floating forest. Schuenemann's departure, however, coincided with the beginnings of a tremendous winter storm on the lake that sent several other ships to the bottom, including the South Shore, Three Sisters, and Two Brothers.

What happened after the Rouse Simmons departed the tiny harbor at Thompson with its heavy load of trees is unknown, but Life Saving Station logs testify that at 2:50 p.m. on Saturday, November 23, 1912, a surfman at the station in Kewaunee, Wisconsin, alerted the station keeper, Capt. Nelson Craite, that a schooner (the Rouse Simmons's identity was unknown) was sighted headed south flying its flag at half-mast, a universal sign of distress. In his remarks on the incident, Craite wrote, "I immediately took the Glasses, and made out that there was a distress signal. The schooner was between 5 and 6 miles E.S.E. and blowing a Gale from the N.W." Craite attempted to locate a gas tugboat to assist the schooner, but the vessel had left earlier in the day. After a few minutes, the life-saving crew at Kewaunee lost sight of the ship.

At 3:10 p.m., Craite telephoned Station Keeper Capt. George E. Sogge at Two Rivers, the next station further south. Craite informed Sogge that a schooner was headed south, flying its flag at half-mast. Sogge immediately ordered the Two Rivers surfmen to launch the station's powerboat. The boat reached the schooner's approximate position shortly thereafter, but darkness, heavy snow, and mist obscured any trace of the Rouse Simmons and its crew. The schooner had vanished.

Barbara Schuenemann and her daughters were concerned when the Rouse Simmons failed to arrive in Chicago Harbor on schedule. However, it was not uncommon for a schooner to pull into a safe harbor to ride out a storm and then arrive days later at its destination. The family's worst fears were realized days later, when still no word of the vessel had been received. Over the next weeks and months, remnants of Christmas trees washed ashore along Wisconsin's coastline. Astonishingly, the lake continued to give up clues long after the vessel's loss. In 1924 some fishermen in Wisconsin hauled in their nets and discovered a wallet wrapped in waterproof oilskin. Inside were the pristine contents that identified its owner as Herman Schuenemann, the captain of the Rouse Simmons. The wallet was returned to the family.

What caused the disaster that befell the Rouse Simmons? There are several theories, but most likely a combination of circumstances or events drove the ship under in the heavy seas. Among the factors are the possibility that the vessel lost its ship's wheel in the storm, its poor physical condition, heavy icing and snow on the vessel's exterior and load, plus the load of 3,000–5,000 evergreen trees itself.

A recent underwater archaeological survey, conducted in July and August 2006 by the Wisconsin Historical Society, discovered that the Rouse Simmons's anchor chain, masts, and spar were all lying forward beyond the bow of the wreck. The location of these items suggest that the schooner's weight was in the bow, causing it to nose-dive into the heavy seas and founder. Another explanation may be that the masts, rigging, and chains were all shoved forward when the vessel dove into the lake bed during its descent to the bottom.

After the schooner's loss, the vessel's sailing condition came under scrutiny. One of the legends associated with the disaster was that prior to its departure from Thompson, rats living aboard the now-dilapidated ship were seen making their way to dry land, as if they had a premonition of its doom.

Moreover, some of the crew was rumored to have deserted the ship prior to its departure. There is some disagreement over the exact number and the identities of the crew members aboard the Rouse Simmons, but newspaper accounts following the tragedy provide evidence that those aboard the vessel included Captain Schuenemann; Capt. Charles Nelson, who was part owner of the schooner; and approximately 9 or 10 other sailors. Some estimates place the number of men aboard the ship as high as 23, when it was said that a party of lumberjacks had secured their passage back to Chicago.

Following the tragedy, Barbara and her daughters continued the family's Christmas tree business. Newspaper accounts suggest that they used schooners for several more years to bring trees to Chicago. Later, the women brought the evergreen trees to Chicago by train and then sold them from the deck of a docked schooner. After Barbara's death in 1933, the daughters sold trees from the family's lot for a few years.

The loss of the Rouse Simmons, however, signaled the beginning of the end for schooners hauling loads of evergreens to Chicago. By 1920, the practice of bringing trees to Chicago via schooner had ceased. Just a few years later, the majority of the once-proud schooners lay leaking and decaying, moored in their berths around the lake.

Over the years, the schooner's disappearance spawned legends and tales that grew ever larger with the passage of time. Some Lake Michigan mariners claimed to have spotted the Rouse Simmons appearing out of nowhere. Visitors to the gravesite of Barbara Schuenemann in Chicago's Acacia Park Cemetery claim there is the scent of evergreens present in the air.

Today the legend of Captain Schuenemann and the Christmas Tree Ship appeals to a large and varied audience, but children seem most attracted to the story. Perhaps the allure of a heart-warming story mixed with shipwrecks, Christmas, ghosts, and Lake Michigan's many mysteries proves irresistible to children of all ages. At least four histories, two documentaries, and several plays, musicals, and folk songs have been written or produced about the legendary ship and its captain and crew.

Each year in early December, the final voyage of Captain Schuenemann and the Rouse Simmons is commemorated by the U.S. Coast Guard Cutter Mackinaw, which makes the journey from northern Michigan to deliver a symbolic load of Christmas trees to Chicago's disadvantaged. Captain Schuenemann and the crew of the Rouse Simmons would be proud.

The History Of Brownhelm Community Christmas

Brownhelm Community Christmas takes place December 24th, annually. Santas visit all homes in Old Brownhelm delivering gifts, candy and fruit.

Brownhelm Community Christmas takes place December 24th, annually. Santas visit all homes in Old Brownhelm delivering gifts, candy and fruit.The History Of Vermilion River Reservation

In 1817, Benjamin Bacon settled with his family along the top of the cliffs overlooking an oxbow in the Vermilion River that would eventually be called Mill Hollow. Soon afterwards, and at an early age, Benjamin was elected to the prestigious position of Justice of the Peace, and in 1824 was selected as one of the first commissioners for Lorain County. In 1835 he purchased an interest in a saw and grist mill that had been relocated to the oxbow in the river. A mill race was cut across the oxbow to increase the water power that turned the mill’s large water wheel. The mills were very successful and by 1845 had provided Benjamin the means to build a nice house across the road. When he died in 1868 at the age of 78, the house and mills were sold to John Heymann, a German immigrant new to the area.

In 1817, Benjamin Bacon settled with his family along the top of the cliffs overlooking an oxbow in the Vermilion River that would eventually be called Mill Hollow. Soon afterwards, and at an early age, Benjamin was elected to the prestigious position of Justice of the Peace, and in 1824 was selected as one of the first commissioners for Lorain County. In 1835 he purchased an interest in a saw and grist mill that had been relocated to the oxbow in the river. A mill race was cut across the oxbow to increase the water power that turned the mill’s large water wheel. The mills were very successful and by 1845 had provided Benjamin the means to build a nice house across the road. When he died in 1868 at the age of 78, the house and mills were sold to John Heymann, a German immigrant new to the area.The History of Gore Orphanage & Swift's Hollow

It's a nightmarish scene in the countryside of Vermilion on Gore Road over one hundred years ago. A gigantic fire engulfs an old orphanage burning dozens of young children alive. Desperate to escape the inferno, the children on the second floor found the stairs blocked by flames. Dreadful screams of the children trapped inside the blazing building pierce the ears of horrified onlookers unable to stop the carnage. The deadly destruction continues until the screams finally fall silent and the only sound that lingers is the crackling and roar of the hellish flames. The smoke ascends into the night sky, carrying with it the souls of over 100 poor orphan children. The building is soon reduced to a pile of glowing embers with only a remnant of the foundation and stone pillars forever preserved for future generations to happen upon.

It's a nightmarish scene in the countryside of Vermilion on Gore Road over one hundred years ago. A gigantic fire engulfs an old orphanage burning dozens of young children alive. Desperate to escape the inferno, the children on the second floor found the stairs blocked by flames. Dreadful screams of the children trapped inside the blazing building pierce the ears of horrified onlookers unable to stop the carnage. The deadly destruction continues until the screams finally fall silent and the only sound that lingers is the crackling and roar of the hellish flames. The smoke ascends into the night sky, carrying with it the souls of over 100 poor orphan children. The building is soon reduced to a pile of glowing embers with only a remnant of the foundation and stone pillars forever preserved for future generations to happen upon.The History of Brownhelm Township

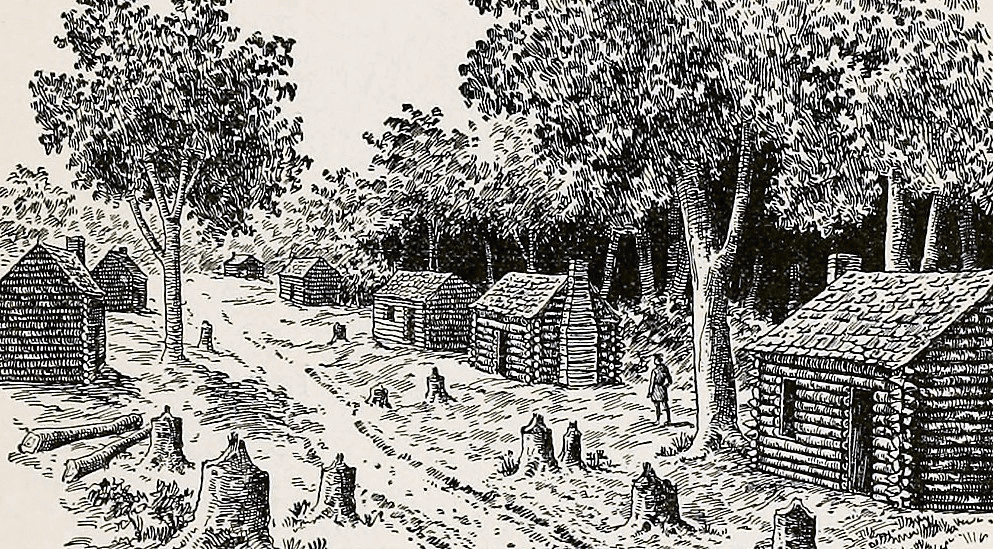

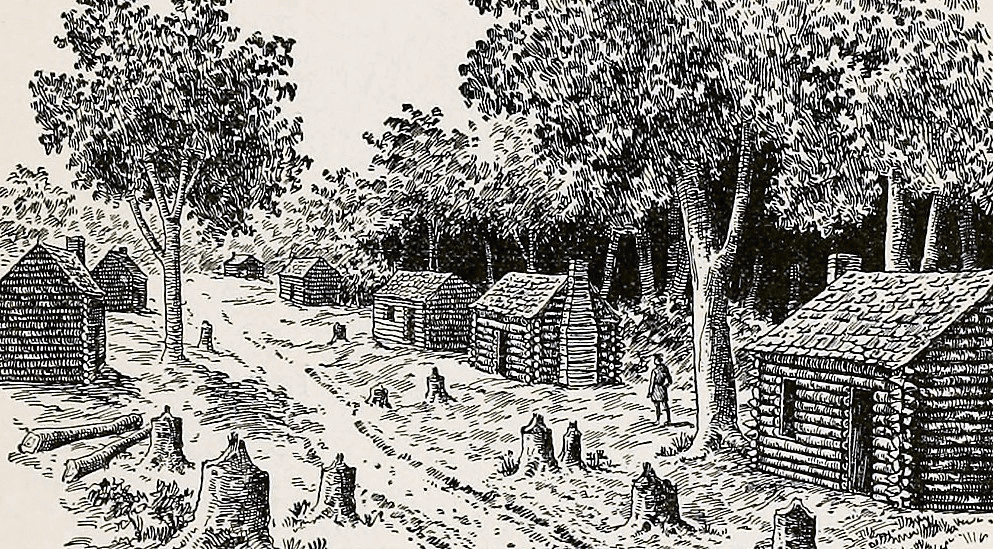

Brownhelm Township Ohio Early Settlement

Brownhelm Township Ohio Early Settlement

The Early Settlers of Brownhelm Township Ohio

Col. (Judge) Henry Brown

William Alverson

- Emily Louisa- born April 30, 1820 in Brownhelm, Ohio; died September 2, 1882 in Lee, Massachusetts

- Mary Lucinia - born September 24, 1821; died April 18, 1840 in Stockbridge, Massachusetts

- Daniel Fairchild - born February 19, 1823; died December 5, 1893 in Canandaigun, New York (On June 15, 1848 Daniel Fairchild Alverson married Sarah Cowdery (1822-1906) in Rochester, Monroe Co., New York. Sarah was the daughter of the celebrated frontier printer and editor, Benjamin Franklin Cowdery (1790-1867).)

- Elizabeth Elvira - born February 8, 1825; died April 1895 in Brownhelm, Ohio

- Frederick William - born December 14, 1829; died August 1894 in Canadaigun, New York

- Julia Harriet - born March 17, 1834, Stockbridge, Massachusetts; died March 8, 1861 in Lee, Massachusetts

Grandison Fairchild

Deacon Shepard

Stephen James

Orrin Sage

Bacon

Enos Cooley

Elisha Peck

Deacon George Wells

John Graham

Abishai Morse

Ira Wood & Stephen Goodrich

Early Life In Brownhelm Ohio

The Grand Old Forest Of Brownhelm

Clothes & Shoes

Food

Black Salts

Wild Animals

One of the features of early life here was familiarity with the wild animals that had possession of the country. The howl of the wolf at night was as familiar as the whip-poor-will’s song - not the small prairie wolf so well known at the west, but the powerful wolf of the forest, the black and the gray. They passed in droves by the dwellings at night, sometimes when the new comers had only a blanket suspended in the opening for the door. Sometimes they crowded upon the footsteps of a belated settler, passing from one part of the settlement to another, The boy crossing the pasture on a winter morning would often see the blind track of a wolf that had loped across the night before. If he had forgotten to bring in his sheep at evening, he might find them scattered and torn in the morning. A dog that ventured from the house at night, sometimes came in with wounds more honorable than comfortable. The wolf was a shy animal, seldom showing itself by day light.

Probably not one in a dozen of the early inhabitants ever saw a wolf in the forest; yet these animals roamed the woods around Brownhelm for years. Mr. Solomon Whittlesey once snatched his calf from the jaws of a wolf, at night, with many pairs of hungry eyes gleaming upon him through the darkness. In 1827, the county commissioners offered a bounty for wolf scalps - three dollars for a full-grown wolf, and half the sum for a whelp of three months. Whether any drafts were ever made upon the treasury does not appear.

Now and then a wolf was taken in a trap or shot by a hunter. Probably less than a half-dozen were ever killed in the township. About the winter of 1827-28, wolf hunts were organized in the region on a grand scale, conducted by surrounding it tract of country several miles in extent, with a line of men within sight of each other at the start, and approaching each other as they moved toward the center. The first of these hunts centered in Henrietta, and resulted in bagging large quantities of game, but never a wolf. A single wolf made his appearance at the center, and was snapped at and shot at by many a rifle, but he got off with a whole skin.

The sport involved danger from the cross-shooting as the line drew near the center, and Park Harris, of Amherst, mounted on a horse, received a shot in the ankle. To avoid this danger, the next hunt centered on the river hollow, about the mill in Brownhelm, but the scale on which it was arranged was too grand to be carried out. The lilies were too extended and broke in many places, resulting in gathering upon the flat a small herd of deer and a solitary fox, barely furnishing an occasion for the hundreds of huntsmen above to discharge their pieces, as the frightened animals escaped into the woods up the river. It was an utterly fruitless chase. A more exciting chase was the slave-hunt of a later day, in which the people bewildered and foiled the kidnappers.

Bears were less numerous than wolves, but they were perhaps more often seen. One was shot by Solomon Whittlesey, from the ridge, a little east of the burying ground. One of the trials of childish courage was to pass the tree against which tradition said that he rested his rifle in the shot. Another dangerous tree was the large basswood that leaned over the brook, a little to the south-east of Harvey Perry’s orchard. Mrs. Fairchild, going over the ridge to bring a pail of water from the spring, once drove a large black animal before her which she thought a dog until he scrambled up that tree when she returned home without the water. The tree stood close by the track that led to Mr. Peck’s, and it was a test of pluck for a child to pass that tree just as the evening began to darken. One day, one of a half dozen sheep was missing. In looking for the lost animal, a place was found where it seemed to have been dragged over the fence where a bear had made his feast, leaving the wool scattered about and a few large bones. The tracks were still fresh in the mud.

Such occurrences gave a smack of adventure to child life in the new country, and it was a matter of every day consultation among the boys, what were the habits of the various animals supposed to be dangerous, such as the wolf, the bear, the wild cat, and the panther, and by what tactics it was safest to meet them. Similar discussions were had in reference to the Indians, who had required a bad reputation during the war, then recent, with England. The prevailing opinion was, that any fear exhibited towards an Indian, or a wild beast, put one at a great disadvantage.

Deer were far more plenty than cattle, and the sight of them was an everyday occurrence. A good marks man would sometimes shoot one from his door. The same was true of wild turkeys. Raccoons worked mischief in the unripe corn, and a favorite sport of the boys was “coon hunting” at night, the time when the creature visited the corn. A dog traversed the cornfield to start the game, and the boys ran at the first bark of the dog, to be in at the death. When the animal took to a tree, it was cut down, or a fire was built and a guard set to keep him until morning, when he was brought down by a shot. The motive for the hunt was three-fold - the sport, the protection of the corn, and the value of the skin; the raccoon being a furred animal.

The greatest speculation in this line of which the town can boast, was made by Job Smith, “a man of some note.” He is said to have bought a quantity of goods of a New York dealer, promising to pay “five hundred coon skins taken as they run,” naturally meaning an average lot. The dealer, after waiting a reasonable time for his fur, came on to investigate, and inquired of his debtor when the skins would be delivered. “Why,” said Mr. Smith, “you were to take them as they run; the woods are full of them; take them when you please.” The moral of the story would not be complete with out stating that the same Job Smith was afterwards arrested as a manufacturer of counterfeit coin.

Thrifty men pursued the business of hunting as a pastime. The only man in town, perhaps, to whom it afforded profitable business, in any sense, was Solomon Whittlesey. Other professional hunters were shiftless men, to whom hunting was a mere passion, having something of the attractions of gambling. Mr. Whittlesey did not neglect his farm, but he knew every haunt and path of the deer and the turkey, and was often on their track by day and by night. He reported the killing of one bear, two wolves, twenty wild cats, about one hundred fifty deer, and smaller game too numerous to specify. One branch of his business was bee hunting, a pursuit which required a keen eye, good judgment and practice. The method of the hunt was to raise an odor in the forest, by placing honey comb on a hot stone, and in the vicinity another piece of comb charged with honey. The bees were attracted by the smell, and having gorged themselves with the honey, they took a bee-line for their tree. This line the hunter observed and marked by two or more trees in range. He then took another station, not on this line, and went through the same operation. Those two lines, if fortunately selected, would converge upon the bee tree, and could be followed out by a pocket compass. The tree, when found, was marked by the hunter with his initials, and could be cut down at the proper time.

Another form of the sport of hunting was even more classic, the hunting of the wild boar. For many years there was an unbroken forest, two miles in breadth, running through the township, between the North Ridge and the lake shore farms. This forest became the haunt of fugitive hogs that fed on the abundant mast, or, in Yankee phrase, “shack,” which the forest yielded. These animals were bred in the forest, and in the third generation became as fierce as the wild boar of the European forest. The animal in this condition was about as worthless, for domestic purposes, as a wolf, as gaunt and as savage. Still it was customary, in the fall and early winter, to organize hunts for reclaiming some valuable animal that had become thus degenerate. The hunt was exciting and dangerous. The genuine wild boar, exasperated by dogs, was the most terrible creature in the forest. His onset was too sudden and headlong to be avoided or turned aside, and the snap of his tusks, as he sharpened them in his fury, was somewhat terrible. Two at least of the young men, Walter Crocker and Truman Tryon, were thrown down and badly rent in such encounters, and others had narrow escapes.

The principal fishing ground of the early years was the “flood wood” of the Vermillion. The lake fishing is a modern discovery. It was not known that the lake contained fish that were accessible. Other sports and recreations were few and simple, most of them presenting the utilitarian element. There were logging bees to help a man who had been sick or unfortunate, raisings to put up a log cabin or barn, and militia trainings, which were entered into earnestly by men who had smelt powder in the recent war.

Early Farm Life Of Brownhelm Township Ohio

Early Education In Brownhelm Township Ohio